Unveiling RRHIZ-UP®: Harnessing the Power of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi for Sustainable Crop Production

Written by Fiona Smith Metson, R&D Biological Controller, BSc. Hons. Environmental Science.

The integration of beneficial soil microbe into agricultural systems represents a critical frontier in sustainable crop management. Among these, Arbuscular Mycorrhizal (AM) fungi have emerged as key symbionts capable of enhancing plant productivity, nutrient acquisition, and environmental resilience. RRHIZ-UP®, a proprietary formulation developed by Metson in collaboration with Professor Joanna Dames of Rhodes University, exemplifies the practical application of this symbiosis through a scientifically engineered, granular inoculant designed for broad agricultural use.

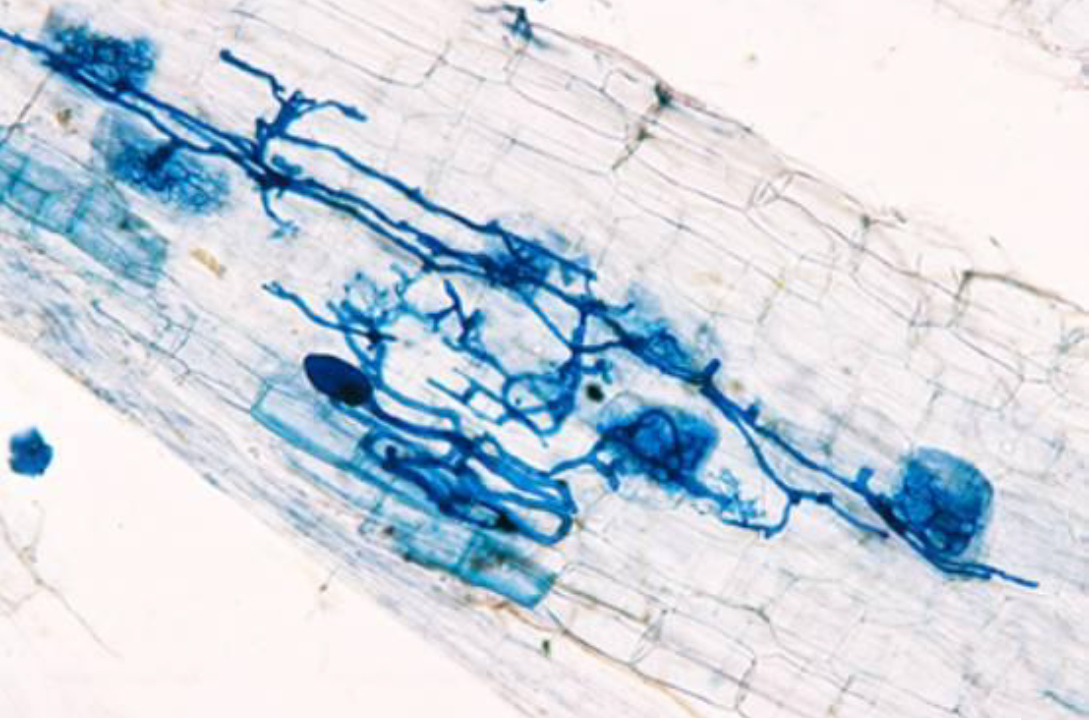

Figure 1: Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal colonisation inside roots, showing typical fungal

At its core, RRHIZ-UP® contains a consortium of four indigenous AM fungal species — Funneliformis coronatum, Funneliformis mosseae, Claroideoglomus etunicatum, and Rhizophagus irregularis. These species were selected based on their proven adaptability to local agro-ecological conditions and their established efficacy in colonising diverse host plants. Upon inoculation, the fungal propagules initiate root colonisation and develop extensive extraradical hyphal networks, facilitating nutrient mobilisation from the rhizosphere. Through these structures, the fungi significantly enhance the bioavailability and uptake of poorly mobile elements, particularly phosphorus, while simultaneously improving plant tolerance to abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, and nutrient limitation.

The formulation of RRHIZ-UP® utilises zeolite as a carrier medium. Zeolite, a naturally occurring aluminosilicate mineral with high cation exchange capacity and porosity, provides a stable environment for fungal propagules. This carrier not only ensures spore protection and prolonged shelf stability but also contributes to improved soil properties following application. Specifically, zeolite enhances moisture and nutrient retention, and promotes aeration within the rhizosphere—conditions that collectively optimise the establishment and persistence of AM fungal networks.

The ecological and agronomic benefits conferred by AM symbiosis are multifaceted. Beyond nutrient transfer, AM fungi contribute to soil structure through the secretion of glomalin, which act as binding agents that stabilize soil structure. Furthermore, AM fungal associations modulate root exudation patterns and microbial community composition, promoting a diverse and functionally balanced soil microbiome. These interactions translate to improved plant vigor, yield stability, and reduced dependence on chemical fertilisers, thereby aligning RRHIZ-UP® with global efforts toward regenerative and low-input agricultural systems.

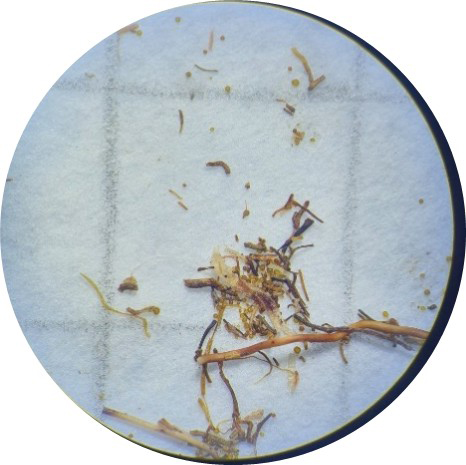

Figure 2: Microscopic image of AM spores and propagules inside of RRHIZ-UP®.

Unlike liquid formulations, the granular composition of RRHIZ-UP® facilitates targeted soil placement and sustained colonisation potential. The product’s stability supports long-term storage without compromising fungal viability, ensuring reliable performance under a variety of field conditions. By prioritising locally adapted fungal strains and collaborating with academic expertise, Metson underscores a science-driven approach to biological product development. RRHIZ-UP® thus represents not merely an inoculant, but a platform for ecological intensification — one that integrates microbial ecology, soil science, and agronomic practice to enhance both productivity and sustainability.

In an era characterised by escalating environmental constraints and increasing food demand, innovations such as RRHIZ-UP® demonstrate the potential of microbial symbioses to transform conventional agriculture. Through the deliberate application of AM fungal technology, RRHIZ-UP® contributes to a paradigm shift toward biologically resilient, resource-efficient, and climate-adaptive farming systems.

Resources

Bonfante, P., Genre, A. 2010. Mechanisms underlying beneficial plant-fungus interactions in mycorrhizal symbiosis. Nature Communications 1:1-11.

Eroglu, N., Emekcib, M., Athanassiou, C. G. 2017. Applications of natural zeolites on agriculture and food production. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 97: 3487-3499.

Grant, A. 2021. What Is Zeolite: How To Add Zeolite To Your Soil. https://www.gardeningknowhow.com/garden-how-to/soil-fertilizers/zeolite-soil-conditioner.htm Date of access: 08 Feb. 2024.

Hawley, G. L., Dames, J. F. 2004. Mycorrhizal status of indigenous tree species in a forest biome of Eastern Cape, South Africa. South African Journal of Science 100: 633-637.

Polat, E., Karaca, M., Demir, H., Naci Onus, A. 2004. Use of natural zeolite (clinoptilolite) in agriculture. Journal of Fruit and Ornamental Plant Research. Special ed. 12:2004: 183-189.

Redecker, D., Kodner, R., Graham, L. E. 2000. Glomalean fungi from the Ordovician. Science 289 (5486): 1920-1921.

Smith, S. E., Read, D. J. 2006. Phylogenetic distribution and evalution of mycorrhizas in land plants. Mycorrhiza 16:299-363.

Szerement, J., Ambrożewics-Nita, A., Kędziora, K., Piasek, J. 2014. Use of zeolite in agriculture and environmental protection. A short review. Institute of Agrophysics PAS, Lublin Poland.