6 Lessons for Sales and Marketing

By Cindy Snyder

Contributor

Biological controls are the fastest growing segment in crop protection, but it’s still a fledgling technology for major row crops. Marketing companies can learn key lessons from early adopters on how to understand and sell thee technologies.

Farmers considering using a biological fungicide to control white mold in a field of edible beans or sunflowers are weighing many of the same factors greenhouse operators did a when they first considered using predatory mites to control spider mites more than 25 years ago.

Namely, what if this doesn’t work?

Growers and horticultural producers alike have become accustomed to applying chemical products that give repeatable and reliable results across a field. But biological products are based on living organisms, and living organisms are sensitive to the environment.

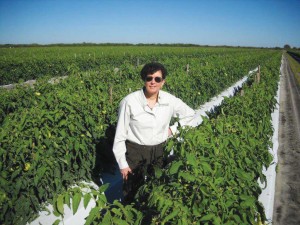

A comparison of treated and untreated bean plants.

Release predatory mites in a greenhouse that is too hot or too cold, and the beneficials won’t be able to build a population great enough to make a dent in the spider mite numbers. Likewise, wait to release the beneficials until the spider mites are out-of-control, and even if the environment is perfect, and the beneficials will never catch up.

“There is a risk,” said Jan Mostert, soft technology portfolio manager for Certis Europe. Sometimes the early biological spider mite controls didn’t work. But 30-some years later, biopesticide use is not only possible in both horticultural and field crops; it is increasingly becoming easier to include ‘soft’ pesticides into an integrated pest management program.

Here are some lessons early adopters learned that can be applied to field crops.

1. It’s a Journey

“You don’t start with a perfect program,” Mostert says. “You start with the idea of getting less dependent on chemical products.”

Spider mites, for example, are very difficult to control because of how quickly the population can build and how easily the mites develop resistance to chemical products. Through trial and error, producers learned which predatory mites worked best and when to release the predators.

Mostert

Finding a supply of those beneficials was difficult until businesses were developed to mass produce predators. Meanwhile, researchers were developing softer products that could be used in conjunction with beneficial insects to bring spider mites under control.

“It took 10 years or so to have enough beneficials plus the IPM products for a complete program,” Mostert said.

Growers also needed time to become comfortable with the idea that unlike broad spectrum products, IPM products wouldn’t kill all the spider mites. Although growers would find spider mite hot spots in their greenhouse, predatory mites had also survived the softer treatment and were ready to feast on the

spider mites.

2. Think Long Term

Chemical-based compounds have given farmers a just-in-time ability to treat pest problems. Biopesticides don’t offer that luxury, especially when controlling diseases.

Bacillus, for example, can be used to control Fusarium in both horticultural and field crops but it must be either applied to the soil or used as a seed treatment to allow the spores to colonize before plants begin wilting.

Another example is Coniothyrium mintans, which acts as a parasite on the hard resting structures of sclerotia (the pathogen that causes white mold) in the soil. Studies have shown that Coniothyrium mintans will destroy up to 95% of the sclerotia in a soil layer, but it takes two to three months to reach that level of control.

“That’s the one thing a farmer always wants: if I apply it, it should work,” said Ketan Mehta, founder of Ecosense Labs in India. “They are so used to working with chemical products they want instantaneous results. That’s something microbials won’t provide.”

3. Follow Directions

The oft-repeated directive to read and follow label directions is just as important for biopesticides as it is for conventional products. Temperature and moisture are critical factors when storing and applying biopesticides because many are derived from living organisms. Providing nutrition or an acclimation period might improve control when releasing biological insects or microbials, for example.

“We’re not looking at just another product that you put on and hope it works,” said Mostert. “You need to introduce it at the right time or day or with the right climate conditions. It’s a mentality shift for the grower to think of biopesticides as a living organism.”

But those restrictions can also make using biopesticides seem like more work than its worth, especially when farmers start considering that the microclimate along the sandy ridge of a field is not the same as the border nor the wet corner. Vegetable growers have the same problems with hot and cold spots in their greenhouses.

Mehta

“That’s one reason why people say the effectiveness (of biopesticides) is a little iffy,” Mehta said. “Once the product is applied, a farmer doesn’t have that much control over the microclimate on the leaves or stems of plants.”

So start by storing and applying the biopesticide in the most favorable manner.

4. Ask Questions

Many of the questions Pam Marrone gets are the same that conventional pesticide representatives get asked nearly every day: What rate should I use, how do I tank mix it, what product can I replace this with in a tank mix?

Marrone

“Farmers want to know how to use them (biopesticides) but don’t know how,” said the CEO of Marrone Bio Innovations, headquartered in Davis, Calif. Her company trains both employees and the retailers who carry their products to help answer those basic questions.

One of the greatest challenges facing biopesticides for field crops are the low barriers of entry into the market. Anyone can identify a microbe, brew up a batch of something, put it on a crop and say they saw a benefit. With large agrichemical companies beginning to introduce their own products, many smaller companies are rushing to bring products to the market.

Marrone, Mehta and Mostert all strongly recommended that growers choose products that have undergone the rigorous testing required to be registered by federal regulatory agencies.

“There are some snake oils out there,” Marrone said. “Look to see how much data is behind the product. Is it just testimonials or is there refereed data? If a company is not willing to tell you as much of the science behind the product as they have, or if they say that’s our secret, that’s a red flag.”

Unfortunately, extension specialists who have often provided unbiased information to U.S. farmers about the efficacy of new products are also low on the learning curve when it comes to biopesticides. Many are beginning to include biopesticides in their research trials but often as a head-to-head comparison rather than part of an integrated program. As that changes, farmers will have access to more information just as greenhouse growers did.

Mostert believes that, thanks to the Internet, crop farmers will be able to adopt softer pesticides at a much faster rate than their horticultural counterparts did. “The conversion will go quicker, better in fields because of the better exchange of information,” he said.

5. Handle With Care

While biopesticides do need to be handled with care, most are not as fragile as people think or as they were 30 years ago.

“Most biopesticides are robust and can be tank mixed,” Marrone said. She points to Bacillus spores as an example. “Bacillus is pretty tough.”

6. Be a Believer

Consumer concerns over residue on produce and mandates to improve worker safety helped fuel the initial interest of horticultural producers to use softer pesticides. But just as greenhouse operators had to find new ways to cope with resistant spider mites, crop farmers are beginning to see pests, like corn rootworm, developing resistance to common control methods.

Still, finding that balance between reliance on chemicals and integrating biopesticides into a control program will require an investment of time to learn about the new options and a willingness to test those options.

“You need to be a little bit of a believer to learn by doing,” Mostert said.