China Price Index: The ‘Invisible Hand’ That Is Reshaping Crop Protection Market Strategy

Editor’s note: Contributing writer David Li offers a snapshot of current price trends for key herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides in the Chinese agrochemical market in his monthly China Price Index. Below he also provides insight into how Bayer Crop Science’s innovative strategies and the shifting landscape of crop protection are reshaping the industry’s future. This article also delves into the challenges faced by multinationals, the rise of Chinese agrochemical companies, and the dynamic interplay of innovation, market demands, and organizational transformation.

During the Warring States period in ancient China, the King of the state of Yan asked his ministers how to govern the country. Guo Wei, one of the ministers of Yan at that time, advised the King that, “The ministers of an empire should be able to be the emperor’s teachers; the ministers of a small kingdom can only be the king’s friends; the local hegemon only treats his ministers as his guests; and the leader is in a crisis mainly because he treats his ministers as his tools of management only. As for how to govern the country, my lord, you can make your own choices.”

In the current crop protection market, we are seeing a lot of companies looking to stimulate the ambitions of their teams. The management of multinational companies hope that they can mold their corporate culture to resemble a startup team, thus making the leap “from zero to one.” This is easy for small teams to achieve. But once the system gets big, the organizational structure inevitably becomes a bloated bureaucracy with lagging decision-making. The advantage of a bloated bureaucracy is that it circumvents the consequences of individual arbitrariness on the functioning of the company, since the priority of a large organization is to reduce risk. For such a team, managing risk is more important than making decisions.

Bayer Crop Science is actively promoting the DSO (Dynamic Shared Ownership) model to facilitate the change of decision-making mechanism in the organization. The core of Bayer’s change is two-fold: one is to emphasize the importance of R&D and innovation as well as product teams, and the other is to strengthen the weight of the customer facing teams around the world. For the Bayer Crop Protection team, the leaders wanted to establish internal decision-making and collaboration mechanisms with mission as the core objective through a flat organizational structure.

This was clearly a positive response by Bayer to the changing market environment in the midst of an industry downturn. But making decisions is more difficult to achieve than downsizing an organization. Start-up teams are able to develop new businesses because they are constantly in trial and error, or as we call it A/B testing. The founder’s job shall be more about finding the right people who can help the organization to excel and raise capital. For multinationals, financing is not the big issue, the lack of talent is. From the perspective of screening people, multinational companies like Bayer are more inclined to choose the “silver spoon,” those with a magnificent career background of the managers than the maverick of the real genius in its management system. Almost all multinational companies, not just Bayer Crop Science, base their selection on such criteria.

However, it is doubtful that such a selection mechanism can really bring real core competitiveness to multinational companies’ systems. Except for learning from other companies’ operational experience, the “silver spoon” may not bring fundamental changes. For startups, however, founders are looking for people who can get things done. They want people who can think independently and deeply. Only in this way, the organization can be dynamic enough, not just a collection of tools. And genius never needs to be stimulated. They can focus on missions and find their own way to achieve the milestones. Matching the talent evaluation system with the DSO model may be a key challenge for Bayer Crop Science in the future.

Another key point for Bayer’s change is whether the company’s decision-making system allows for different voices to exist? Frontline employees have their own opinions about the evaluation of external resources and circumstances as they are exposed to them for a long time. These insights may deviate from the perceptions of Bayer Crop Science’s management. Does Bayer’s leadership allow for deviation? Can the team make the right decisions by confirming or disproving them?

In my work with different multinationals, I have found that inherent perceptions in individual companies are difficult to break from within. The reason is that promotion within large companies is based on saying “yes.” Therefore, denying a superior’s opinion may be the end of an employee’s career. If there is not enough tolerance for internal dissenters, the flat organizational structure may only be superficial to the company’s mission-oriented and collaborative mechanism. The inertia of the internal mindset of a company is difficult to break, and this may be the so-called innovator’s dilemma.

The market landscape in the first quarter of 2024 was tougher as compared to last year. The performance of various multinational companies was impacted by de-stocking as well as in-time purchases in the global crop protection market.

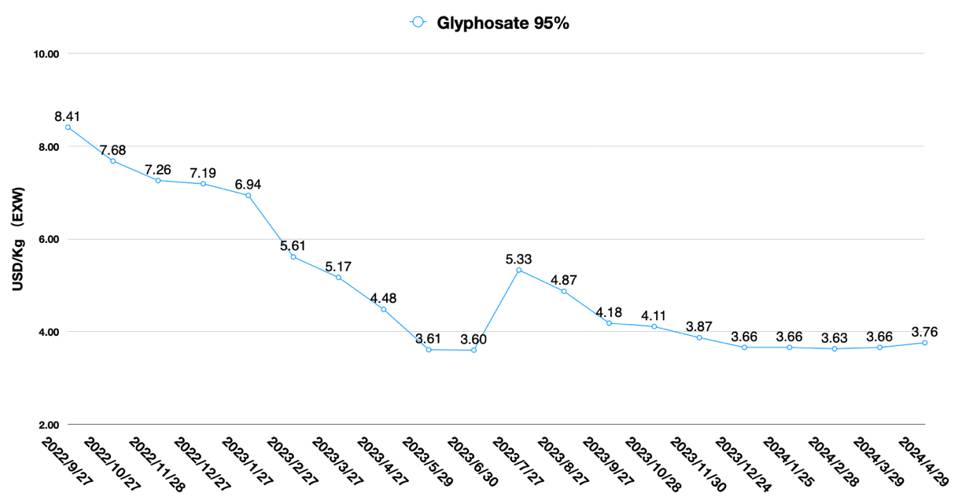

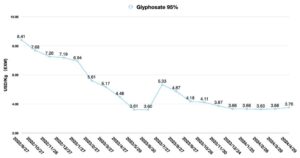

Bayer Crop Science exchanged its low-price strategy for glyphosate for a 49% increase in sales volume in Q1 2024. But low glyphosate prices have always been a dilemma for the company. The company is fully supporting corn seed sales thereby securing margins. Bayer is also laying out future launches of new herbicides. Corteva has benefited from increased seed prices to compensate for lower crop protection sales. Its pre-channelization of biologics enabled the company to generate significant gains in the Brazilian market. Syngenta’s sales declined in all regions except China, where sales increased 14%.

The increased sensitivity of the farmer’s balance sheet has impacted the decline in multinationals’ performance. Farmers are voting with their cash in hand, choosing decisions that are in their favor. This change in consumer behavior is also causing concern among multinational teams. They worry that their bureaucracies will not be able to adapt to such changes in consumer behavior. But consumers are not giving management teams much room to maneuver, either by lowering COGS (Cost of Good Sales) or by bringing disruptive innovations to farmers. Disruptive innovations are extremely difficult to realize in the short term, but it is possible to reduce operating costs quickly. This coincides with a strategic shift in governance within Bayer.

The ambitions of Chinese manufacturers for future business development, as opposed to overseas multinationals, have also raised concerns among some global practitioners. Whether it is the technological or production advantages of Chinese companies, it seems to be threatening the growth of the global agricultural economy. But is this really the case? With agricultural prices on the decline, low input prices are a boon to farmers themselves. In addition, behind the scenes of high-growth crop protection companies are those that are taking full advantage of China’s supply chain for their AIs. The profit margins of Chinese companies are relatively weak compared to the margins gained from branded products and channel ownership. It is the distribution of profits between supply and channel that analyzes who is the ultimate profiteer. Farmer cooperatives that work directly with Chinese suppliers may better understand this.

The challenge that Chinese companies pose for the world may be even greater in that their strengths are accelerating the need for deep change in global crop protection companies. In a free market economy, any company can make any legally compliant investment. For Chinese agrochemical companies, they are no exception in their active participation. Changes in consumer behavior may give Chinese pesticide companies a historic opportunity. They are becoming more pragmatic in their desire to build links with real users, let the advantages of the Chinese supply chain be passed directly to the farmers. Because this way they will not be isolated from the global agrochemical market by the “out of China” strategy of some crop protection executives.

It is worth mentioning that the disorderly development of Chinese pesticide enterprises in the early days of reform and opening up has long been thrown into the recycling bin of history. Chinese enterprises are improving their environmental facilities and can already meet the requirements of every multinational company. Otherwise, they would not be able to enter the global supply chain system. As China and the world move toward carbon neutrality, Chinese companies are actively cooperating with multinationals to invest in energy conservation and emissions reduction. Chinese agrochemical companies’ social responsibility is becoming their new competitive edge. Surprisingly, Chinese companies can still make a profit even with the same level of waste treatment and huge investments in energy efficiency as multinationals. This is hardly convincing in the eyes of the prejudiced. But Chinese suppliers have made or are making the move.

So, there’s one question we can’t avoid: Is China’s over capacity sustainable? The answer is indisputably no. Matching capacity to demand requires a pullback. During the global pandemic, China supply was raised by higher safety stocks and early panic buying, that was the driving force behind Chinese companies’ continued investment in capacity.

However, it is certain that the invisible hand of market demand is accelerating the reset of the supply chain pendulum. Many Chinese agrochemical companies are extremely cautious about investing in new capacity in 2024. As a result, even though some suppliers have announced that they would invest in capacity for certain products, the actual implementation of the project still has to be adjusted according to market demand changes. This undoubtedly makes it more difficult for key accounts to manage their supply chains. In any case, for some companies that do not have raw material advantages, production advantages, and R&D advantages, their supply must not be sustainable. The question of which companies or teams will survive this fierce competition, is a difficult one to answer.

Not long ago, a multinational company procurement lead asked me in person, “Can you tell me what the future supply pattern of this product is?” My answer was, “No, I can’t.” After all, I didn’t have a crystal ball with me, and I couldn’t create a magic answer for him. It’s too early to draw conclusions about what companies have capacities that are sustainable. If we analyze only the capacity and cost advantages of the companies, the conclusion will be one-sided. My view is that we need to look at China’s agrochemical companies in a systematic and structured way. However, there is one key assertion I can share. The fact is that the future Chinese supply landscape will be influenced by key accounts, multinational companies, and generic companies. Along with multinationals and generic companies, the ranking of the top 100 pesticide supply companies in China will be rewritten accordingly. China’s supply landscape depends to some extent on the customers’ decision.

As demand shifts, Chinese agrochemical companies are at a crossroads, whether to remain committed to to B or to shift to a C strategy. We need to stratify the issues of such a strategic shift, such as where is the target market for C? Should C product categories mimic the solutions of multinationals, or should they take a different approach by introducing innovative products or biologics? How to measure the value of meeting farmers’ needs by China suppliers? How can the value be sustainably delivered to the Chinese company’s partners in the target market? Do we need to adopt new application methods such as drone crop protection or digital farming? All these questions lead to one key point: What is the frontier of market growth in the target market?

So far, Chinese agrochemical companies are standing on the same starting line as multinationals. Channels and farmers are reshaping the upstream supply chain with their own behavior. Lavoro, Brazil’s largest agrochemical distributor, mentioned in its investor presentation released in May that the company believes its crop care business has several core strengths: first, the direct sourcing of post-patent agrochemicals from Asia at improved costs; second, the robust in-house product registration expertise; and third, the portfolio of 10-plus registered products, expanding to 100+ over the next two to four years. Key distributors in the target markets have awakened. Their focus on Asian AI resources will further squeeze the profit margins of generic products inherent in multinationals and generic companies. Therefore, the paradigm of upstream supply chain management must change for all players.

For multinationals, the core strength is innovation. The launch pace of patented compounds on the market of multinationals is slowing down. For example, Brazilian distributor AgroGalaxy is focusing more on the development of its seed business. It seems that the seed business has higher technological barriers than agrochemicals.

The market channel has shifted from being a buffer zone for sales achievement to a service platform for sustainable growth. This matches the strategy of Chinese agrochemical companies, where cost is a core advantage. Same as multinationals, the key question is will the leadership of Chinese companies be willing to pay for trial and error? If we had to cite examples to learn from, China’s agrochemical industry leaders should visit startups in Shenzhen in various fields. Young teams combined with capital support are helping these dynamic start-ups to try new challenges and internationalization. The young founders there are building their nests like the King of Yan in the Warring States period, with professional talents of all kinds as their teachers. If entrepreneurs in northern China could be still living in the early days of reform and opening up, and entrepreneurs in the south of China are in the mindset of China’s entry into the WTO, Shenzhen’s entrepreneurs are already in sync with the rhythm of global innovation like incubators in U.S. It can be said that Shenzhen is the future of China’s microcosm.

It is true that Chinese agrochemical companies should not limit themselves to serving the purchasing teams of multinationals in China. They should go to the real markets. When you knock on the door of every farmer, I think they should be happy to share with you the problems they are facing. We should be learning from farmers, not using them as operational tools. If you can solve the key problems of some of them in a sustainable and low-cost way, it will be not far from the real maturity of Chinese agrochemical companies.