Will the U.S. Re-Engage the WTO and FAO?

Trade and tariff issues added additional complexities to 2020. In the U.S., the effects recently enacted agreements are starting to be understood. We caught up with Mary Kay Thatcher, Senior Lead of Federal Government Relations for Syngenta, during the Syngenta Media Summit in November to talk about the major issues affecting crop protection manufacturers and retailers during the year, and how those issues are expected to affect business in 2021. As the lead lobbyist for the largest crop protection conglomerate in the world, Thatcher is continually educating legislators and their staffers from various backgrounds about the importance and role of agriculture technology, the benefits of strong agriculture systems, and the regulatory systems that govern them.

Much of the past four years has been focused on trade policy as the U.S. reconfigures many significant trade agreements in key export markets.

The North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement was replaced this year with the U.S.-Mexico-Canada agreement (USMCA), which went into effect on July 1. The USMCA was intended to improve the rules of origin on manufactured goods and benefit U.S. farmers and agribusinesses by modernizing and strengthening food and agriculture trade in North America. The first few months of the agreement have already had their speed bumps:

Thatcher: One of the things we’ve spent a lot of time on is the enforcement of the US-Mexico-Canada agreement, specifically for the U.S. and Mexico. We have a lot of concerns. Within the first six weeks, we already had three enforcement issues with them. One: They wanted to yank glyphosate off the market. Two: They started talking about having 80 other pesticides that they wanted to follow that up with, and they are pesticides that are used broadly. And three: They have incredibly slowed down registrations, label changes, and other things, and it’s costing the industry a tremendous amount of money. Additionally, they’re not approving biotech traits. There are 17 in a holding pattern and 14 of them are late.

Mexico is led by President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, who took office Dec. 1, 2018. The administration opposes GMOs and favors a more restrictive European-style regulatory system when it comes to pesticides. Mexico announced in August 2020 it would phase out glyphosate by 2024 and an evolving list of more than 80 additional pesticides — most of which are restricted for use by at least one other country — are being scrutinized and potentially could be restricted, although it is unclear what legal or regulatory mechanism might be used to re-evaluate or invalidate existing registrations.

The administration is already restricting imports of glyphosate and the raw materials needed to originate the molecule by denying import licenses — normally a routine administrative procedure at the port of entry — as an means to circumvent legal registrations.

Thatcher: We are really concerned that Mexico seems to be waving the flag of the precautionary principle like the EU, which is something we don’t want to see in Mexico and we don’t want to establish precedent on that, either. It doesn’t just affect companies like Syngenta, it will affect farmers, too, because the Mexican government isn’t going to disadvantage their farmers by saying they can’t use a chemistry. They’ll put the leash on [foreign] farmers by restricting imports of produce with MRLs of that substance.

Mexico is taking its lead from the EU, which continues to tighten its maximum residue limits on imported produce to comply with its pesticide restrictions and zero-residue tolerance policies on some AIs. The EU pesticide market has been close to flat for several years in value terms, but volumes are down and will continue to decline under its new Farm to Fork Initiative, which outlines sustainability goals aimed to reduce pesticide use by 50% by 2030 and curb the use of mineral fertilizers by 20%.

Currently about 72 pesticides are banned in Europe that are approved in the U.S. Other countries are following suit. Brazil has banned 17 chemistries that are legal in the U.S., and China has restricted 11. The totality of the bans and tightened residue limits create an unofficial patchwork of de facto standards that farmers must follow to retain access to foreign markets.

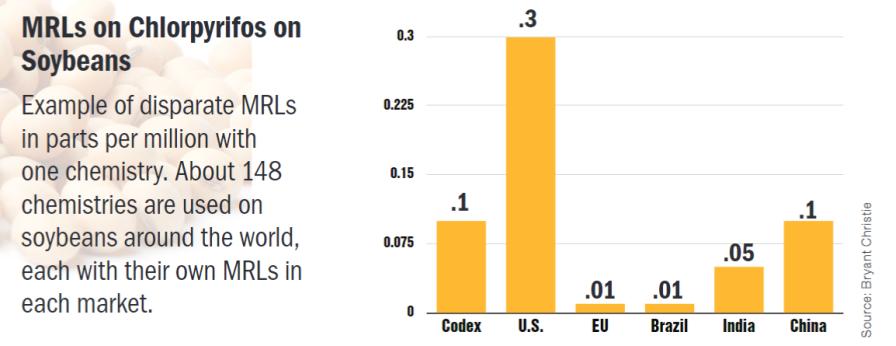

Thatcher: The industry as a whole needs to help farmers understand better just how serious the EU Farm to Fork proposal really is. And we continue to be incredibly concerned about maximum residue levels. It seems like a new country every week adds MRLs to something, and almost every country has MRLs, and some are arbitrary. You have more countries deciding not to use Codex numbers (FAO standards), and then they are implementing legislative-based thresholds on MRLs, which are highly technical.

The changes in MRLs that countries make often affect key commodity crops, including major exports like corn and soybeans. Trade policy further complicates market access and potentially restricts demand for large-area cash crops. The most notable disruption to demand predictability has been with soybeans as a result of ongoing tariff retaliation between the U.S. and China. China has agreed to buy more soybeans from the U.S. as part of Phase 1 of the countries’ new trade agreement, but with the purchase deadline the ended at the end of 2020, it’s unclear (at the time of this writing) whether China would fulfill all its purchase agreements.

On the positive side, China-U.S. discussions appear to be positive and productive, and any delays in the purchasing deadlines look to be influenced more by demand than foreign policy. The WTO could be a more productive forum for arbitration on trade matters going forward, too, providing more recourse to rectify trade disputes. The WTO Committee on Dispute Settlement hasn’t been restaffed by the U.S. in the current administration, effectually gutting the process and forcing countries to establish new framework for trade disputes. But the incoming Biden administration is expected to reinstitute its WTO involvement.

Thatcher: I think Biden will try to make the WTO work again. And I know there are frustrations with it, but it’s the best thing we have right now, especially when it comes to dispute resolution. I’ve been at a lot of WTO meetings, and I’m not sure we’ll ever get back to a high-level multilateral trading agreement again. That might be off the table forever, and that’s too bad, but the other good things the WTO does like dispute resolution need to be fixed.

Trade and MRL harmonization issues provide risk and uncertainty for exporting countries at a time when production costs are rising for farmers, putting pressure on farm profits in tandem with low commodity prices and uncertain demand amid slower global economic growth. As government subsidies, price guarantees, and COVID-19 relief payments are expected to decrease or disappear in 2021, more farmers are at risk of insolvency.

Thatcher: Some farmers are doing quite well right now [in the U.S.], and we have some generally medium-sized farmers that aren’t doing too well, and those guys are going to continue to struggle financially. It won’t look like the 1980s, but financial institutions are tightening, and some farmers are going to have a hard time. Some have been saved by COVID payments, but we don’t think those will continue, so what happens then?