The Sweet Smell of Pheromone Success in Crop Protection

The use of pheromones is projected to rise significantly in crop protection over the next few years, according to two market research organizations.

In January, Research and Markets reported that the integrated pest management pheromones market, from 2021 to 2028, is expected grow at a compound annual growth rate of 12.3% and become a $1.5 billion industry.

DunhamTrimmer, a global market research firm focused exclusively on biological and natural plant protection, forecasts that the use of pheromone products in crop protection will increase at a CAGR of 8.9% worldwide between 2020-2025, with some regions seeing growth of 11% and 15%.

There are several reasons for this growth. Consumers are demanding produce with fewer pesticides. Governments are more strictly regulating pesticides and offering farmers incentives for crop-protection alternatives. Meanwhile, insects are developing resistance to traditional pesticides.

Most significantly, advances in technology have made pheromone production less expensive.

“The investment community is very interested in pheromone technology, and companies have received significant investment dollars to develop it,” says Rick Melnick, Vice President of Global Business at DunhamTrimmer. “Costs are coming down, and as a result, investors are seeing that pheromones have great potential of being used in row crops, and because of their nontoxic endpoint, they also fit into sustainability initiatives going on around the world.”

The PHERA Project, launched in 2020, is a consortium of companies — including BioPhero in Denmark and SEDQ Healthy Crops in Spain — concerned about feeding the world as the population rises. The project is hoping to increase the use of pheromones in crop protection by decreasing the cost of pheromone production. The key is a new production method: Fermentation.

“If we want to feed the world without harming it, we need to talk about sustainable intensification,” says Kristian Ebbensgaard, CEO of BioPhero. “Insect pests constitute a real threat to food security — crop losses caused by pests are estimated at up to 20% globally — and farmers need economical, effective and preferably easy-to-use crop protection solutions.

“Pheromones provide a sustainable alternative to insecticides, and the PHERA Project seeks to develop pheromones with a price that make them attractive to farmers of field crops,” Ebbensgaard says.

Technological Breakthrough

Insects use pheromones to communicate with each other. Different pheromones sound alarms, point to food trails and mark territories. Females secrete sex pheromones to attract potential mates.

In crop protection, artificially produced sex pheromones draw male insects away from real females. They disorient the males, thwart the mating process and thus reduce the insect population without killing. Pollinators and beneficial insects are unharmed.

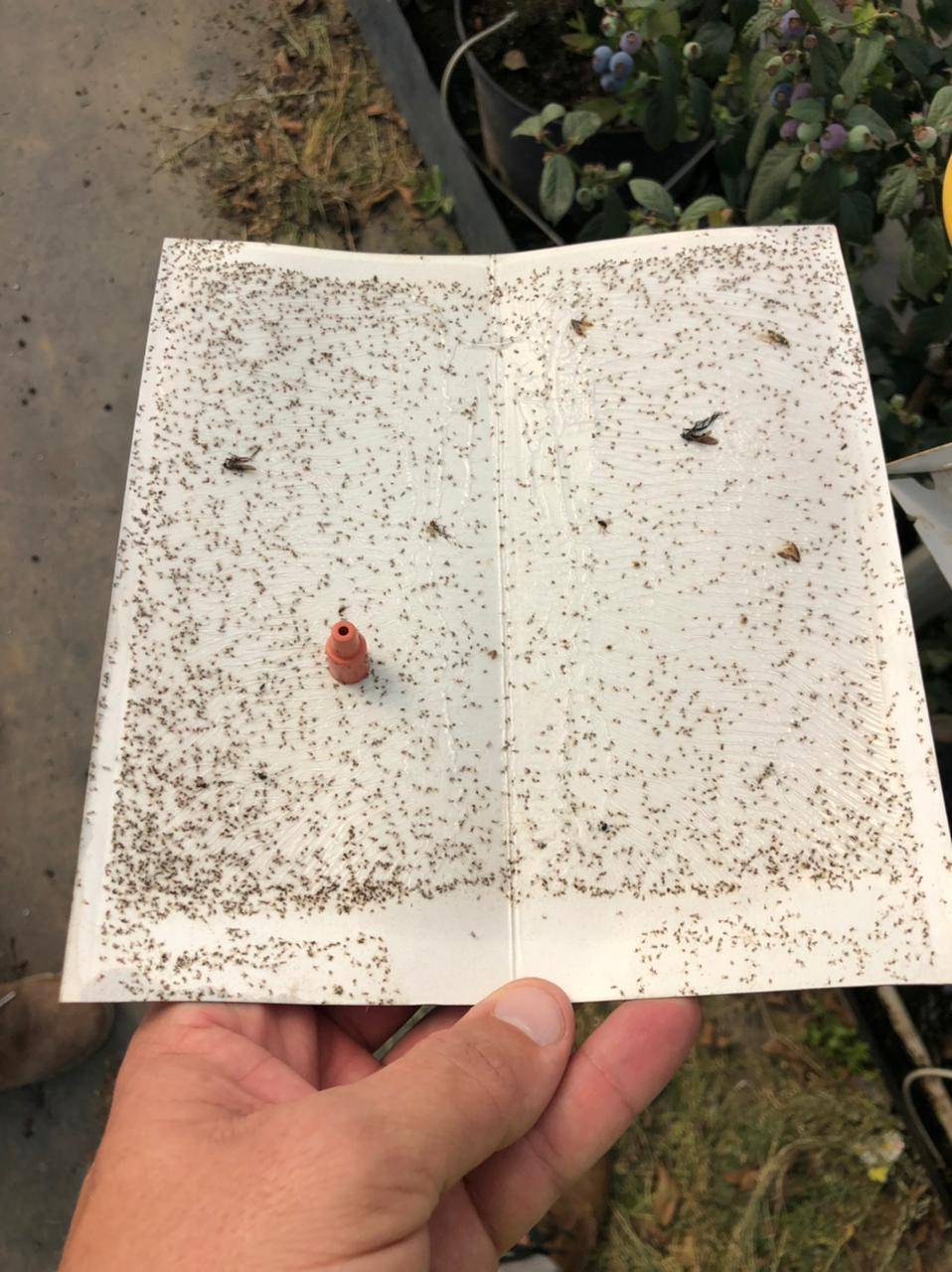

Farmers can spray the nontoxic pheromones or purchase dispensers that release pheromones intermittently. Another option is to use pheromones as bait to trap insects, estimate the population and determine if pesticides are warranted.

Emily Symmes — Senior Manager of Technical Services at Suterra, a maker of environmentally sustainable pest control products, including pheromones, with offices in the U.S. in the state of Oregon and in Spain — says pheromones have successfully managed the populations of several insect species, including codling, diamondback, and Oriental fruit moths, navel orangeworms, vine mealybugs, and California red scales.

Crops protected with pheromones include those in specialty markets, like nuts, pome, stone and citrus fruits, grapevines, and increasingly cole crops.

Marta Melgarejo, Research and Marketing Investigator at SEDQ, says mating disruption can completely replace pesticides in some cases, like with Asiatic rice borers and European grapevine moths in certain regions.

“Even when the elimination of pesticide treatment is not possible, mating disruption could reduce drastically its use, as in the case of the codling moth,” Melgarejo says.

DunhamTrimmer’s Melnick says that historically pheromones were produced through a biochemical process in which analogs of pheromones were synthesized. However, the process was expensive, so only high-valued crops like apples, pears, and grapes were protected with pheromones.

A technological breakthrough developed within the last 10 years stands to lower the cost of pheromone production considerably. It’s called microbial fermentation, and Melnick said it will make pheromones available to row crops for the first time.

BioPhero is adapting yeast fermentation to make pheromones that can economically protect corn, rice, soybean, and other row crops.

“As pheromones are very specific molecules, they are complex and expensive to make using the traditional chemical route,” Ebbensgaard says. “The enzymes in the biochemical route produce pheromones very precisely as part of the biological process. When harnessed in a modern production environment, the biological platform can outperform the synthetic route on cost.”

Consumers and Governments

Other factors driving the pheromone revolution include growing awareness and concern among consumers of how food is grown. Symmes says advocacy groups like Mind the Store, based in Washington, D.C, are ranking grocery chains on how well they reduce chemicals in produce. In turn, grocery chains are asking growers to cut back on chemical use.

“There are more and more details emerging in the common press exposing the dark side of pesticides on human health, and the environmental impact, like honeybees dying,” says Cornelius Oosthuizen, Marketing and Technical manager at Koppert, a Netherlands-based company focused on natural solutions in crop protection.

“Thus, the public’s concerns are growing.”

Governments are acting, too. Symmes says the number of government-restricted or prohibited agrochemicals is increasing, so growers have fewer broad-spectrum pesticides from which to choose. Meanwhile, the European Green Deal’s Farm-to-Fork Strategy calls for reducing the use of pesticides by 50% from 2020 to 2030.

Oosthuizen says pesticide legislation in South Africa has changed little since 1947 but since the country’s agricultural sector relies on exports, it must conform to European standards.

Meanwhile, governments are encouraging alternatives to pesticides. Ebbensgaard says the use of pheromones has been subsidized in some countries, including Spain, France, Switzerland, and Chile. Even after the subsidies stop, farmers stay true to pheromones.

However, experts agreed that pheromones will never completely replace pesticides, at least on a large scale.

“Sometimes you need to stop insects right now,” Melnick says. “You don’t have time to mess with their mating cycles.”

Ebbensgaard says pheromones are one tool in an integrated pest management system.

“In the future, we will see an increase in consumption of biological solutions and a decrease in the use of chemical ones,” Ebbensgaard says. “Clearly, the more insecticide we can replace with pheromones, the better.”