Why Chinese Agrochemical Production May Not Be Sustainable — And How the Global Industry Should Respond

It’s been estimated that as much as 70% of the crop protection chemicals consumed worldwide currently have a Chinese component. We’ve asked ourselves: how sustainable is the current path of the Chinese industry and its domination of global agrochemical production? And, should the industry respond in a way to support the production of crop protection chemicals outside of China?

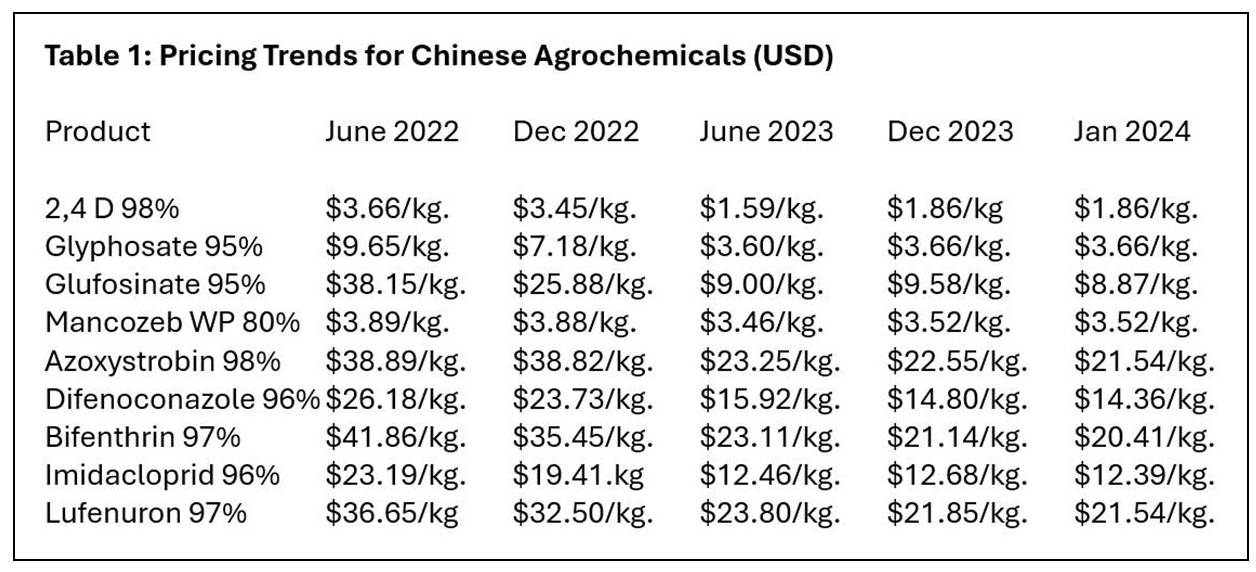

David Li recently presented an excellent webinar for the AgriBusiness Global LIVE! series. Since Li is a true expert in these matters, you are urged to review what he had to say and take it very seriously. Among the information he presented were pricing trends for Chinese agrochemicals (see Table 1). Note the declines — some steep — across all active ingredients in less than two years.

Li’s reporting further shows that many Chinese production companies, much like the rest of the global industry, are running significant deficits. However, China, unlike the rest of the world, is spending tremendous sums to increase its capacity to produce many of these products, especially glufosinate, in spite of falling prices.

Therefore, the industry may want to consider if the current model of Chinese domination of global agrochemical production is sustainable, especially for products of which there are currently “committed” producers outside of China. All of the materials in this chart, with the possible exception of lufenuron, have significant production in many other countries. By the way, this is also true of many other materials that are not on this list. Can factories outside of China survive the enormous amount of pressure being applied by what in many instances is clearly unsustainable pricing?

Three Global Trends Exacerbate the Challenge

In addition to declining pricing and expansion of Chinese production, there are at least three other factors that could quickly exacerbate this challenge even as the world’s population continues to grow:

- New advances in targeted application techniques. Use of drones and smart tractor technologies is likely to lead to a reduction in the use of all classes of pesticides. There are both political and practical considerations that will drive this development.

- Enormous quantities of agricultural commodities are now being diverted into use as fuel. In the case of corn-based ethanol, if the world continues to focus on electric vehicles to replace internal combustion engines, there has to be a point in time —perhaps in the not-too-distant future — when demand for ethanol will decline. While E10 is currently the dominant blend, and many vehicles likely can run on E15. If U.S. legislation tries to go much further, many vehicles will not run properly. In the case of biofuel derived from soy oil, it is likely that usage as an aviation fuel is in its infancy. There is no indication that anyone is even dreaming about electric aircraft. However, usage in trucking could begin to decline as short-haul transport goes electric, and with long-haul trucking perhaps not too far behind. Can electric freight trains be part of the future?

- There are many who believe that farming practices, especially the raising of livestock and the use of fertilizers, are significant factors impacting climate change. These believers are also generally opposed to genetically modified crops and other attributes of modern farm technologies, and also are very concerned about the clearing of forests for increased farm acreage.

Therefore, potential reductions in commodity usage outside of the food chain — coupled with technology that reduces the amount of chemistry that is required per acre, and combined with pressure from global warming activists — could have an impact on the number of acres being planted along with the amount of chemistry applied to those acres.

How Should the Industry Respond?

The U.S. partially responded to this challenge when it imposed 301 surtaxes on certain Chinese products in 2018. Since these levies were imposed at the eight-digit harmonized tariff level, they generally were not product specific. The result is that materials such as glyphosate are not subject to such levies, even though there is a highly competitive glyphosate producer in the U.S. (glufosinate, which is also not subject to any surcharges, was produced in the U.S. up until 2020, but such production has since been shut down.)

Should the U.S. government now consider unilaterally implementing a more targeted, product-specific program?

A study done by Fanwood Chemical last year and published by ABG showed that the 301 surcharges had a very limited impact on sourcing patterns for active ingredients (AIs). This was not a big surprise since the regulatory and financial hurdles to establishing world-scale production of AIs are very high — and especially true because the U.S. was the only country that imposed these levies. However, if there were to be a coalition of countries working together, at a minimum to include the U.S., Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, the European Union, the UK, and Japan, something might then be accomplished to assure the world a variety of sources for important molecules.

Some will note that individual companies have the ability to take protective actions for the products they manufacture in a particular country by filing dumping suits. In the U.S., many such suits have been prosecuted against many Chinese chemicals. Similarly, Chinese companies have filed action against imports into China by a variety of countries with a variety of products. The problem with this approach, if the global industry wishes to maintain multiple sources of agrochemicals, is that the suits are expensive to prosecute, and they only protect the product in the country of manufacturer. Because the supply of crop protection chemicals is and needs to continue to be a worldwide business, and because most factories need to export outside of their home markets in order to be economically viable, a dumping suit filed in the U.S., the EU, or any other land has no impact on any other country nor on the worldwide value of the product.

How Will You Plan?

The Chinese government has publicly stated that it wants to dominate some industries to protect its own interests, and it appears that crop protection is one of the industries on this list. This makes practical sense since a viable crop protection industry is a vital component of food security.

Something to consider: As the Chinese economy resets and recovers after the pandemic, will domestic political intentions target the overproduction of agrochemicals by consolidating or limiting capacity to improve profitability? Only time will tell. What will your plan be in the face of these developments?